https://doi.org/10.35362/rie8413987 - ISSN: 1022-6508 / ISSNe: 1681-5653

Revista Iberoamericana de Educación (2020), vol. 84 núm. 1, pp. 85-108

- OEI

recibido / recebido: 01/07/2020; aceptado

/ aceite: 08/10/2020

Exploring trends in the relationship between child labour,

gender and educational achievement in Latin America

Abigail Middel1 ![]() ; Kalyan Kumar Kameshwara1

; Kalyan Kumar Kameshwara1 ![]() ; Andrés Sandoval-Hernandez1

; Andrés Sandoval-Hernandez1 ![]()

1 University of Bath, United Kingdom

Abstract. Participation in child labour, in both

household and non-household activities, gender effects and low educational attainment

remain challenges for countries in Latin America. Through hierarchical linear

modelling of data from the OECD’s Programme for

International Student Assessment (PISA), this study seeks to explore the

current cross-country trends in the relationship between educational

attainment, child labour and gender. While

non-household labour is found to have an effect, as

per statistical significance and the magnitude, on educational achievement

across all Latin American countries; participation in household labour is significant in only two countries (Peru and

Uruguay). Girls are found to underperform compared to boys by a significant

margin across Latin America. The later part of the study seeks to examine the

interaction effects of gender and participation in labour

activities. Results show that gender has no moderating effect, suggesting that

the participation in work itself or workspace (household or non-household) does

not influence or contribute to gender inequality in education outcomes. The

explanatory factors for gender inequality in education outcomes is potentially

rooted in a different sphere of influence which needs to be deciphered through

deeper empirical investigation.

Keywords: child labour; gender;

inequality; educational achievement; Latin America

Análisis de tendencias en

la relación entre el trabajo infantil, el género y los logros académicos en

Latinoamérica

Resumen. La

participación de menores, tanto en tareas domésticas como no domésticas, los

efectos del género y los bajos logros académicos siguen siendo un reto para los

países de América Latina. A través del modelaje lineal jerárquico de datos del

Programa Internacional de Evaluación de los Alumnos (PISA), este estudio busca

explorar las tendencias entre los países en la relación entre los logros

académicos, el trabajo infantil y el género. Si bien el trabajo fuera del hogar

suele tener un efecto sobre los logros académicos en todos los países de

Latinoamérica, tal como demuestran la importancia y la magnitud de las

estadísticas; la participación en las tareas del hogar es relevante únicamente

en dos (Perú y Uruguay). Se ha visto que las niñas obtienen peores resultados

que los niños en un margen importante en toda Latinoamérica. La última parte

del estudio busca analizar los efectos de interacción de género y participación

en actividades laborales. Los resultados demuestran que el género no es un

factor moderador, lo que sugiere que la participación en el trabajo o en el

lugar de trabajo en sí mismo (en el hogar o fuera de él) no influye ni

contribuye a la desigualdad de géneros en los resultados académicos. Los

factores que explican la desigualdad en los resultados académicos se encuentran

posiblemente en una esfera de influencia distinta que debe descifrarse mediante

una investigación empírica más profunda.

Palabras clave. trabajo

infantil; género; desigualdad; logros académicos; Latinoamérica.

Análise das tendências

na relação entre o trabalho infantil, gênero e desempenho acadêmico na América Latina.

Resumo. A

participação de menores, tanto em tarefas domésticas

como não domésticas, os efeitos

do gênero e o baixo rendimento escolar continuam sendo um desafio

para os países da América Latina. Por meio de modelagem linear hierárquica de dados do Programa Internacional de Avaliação dos Alunos (PISA), este

estudo busca explorar as tendências

entre os países na relação

entre desempenho acadêmico,

trabalho infantil e gênero.

Embora o trabalho fora de casa tenda a afetar o desempenho acadêmico em todos os países da

América Latina, como mostra a importância

e a magnitude das estatísticas,

a participação nas tarefas

domésticas é relevante apenas em dois (Peru e Uruguai). Viu-se que as meninas obtêm piores resultados que os

meninos por uma margem

significativa em toda a América Latina. A última parte do estudo

busca analisar os efeitos

da interação de gênero e a participação nas atividades de trabalho. Os

resultados mostram que o gênero

não é um fator moderador, sugerindo que a participação no trabalho ou no próprio local de trabalho (no lar

ou fora dele) não influencia nem contribui para a desigualdade de gêneros nos resultados acadêmicos.

Os fatores que explicam a desigualdade

nos resultados acadêmicos estão

possivelmente em uma esfera

de influência diferente que deve

ser decifrada por meio de uma pesquisa empírica mais

profunda.

Palavra-chave:

trabalho infantil, gênero; desigualdade; resultados acadêmicos;

América Latina.

1. Introduction

Academic achievement is important because it is strongly linked to

positive outcomes in many other areas. Adults who report high educational

achievement during their school time are more likely to have stable employment,

have more employment opportunities, and earn higher salaries than those with

lower educational achievement (Card, 1999). They are less likely to engage in

criminal activity (Machin et al., 2011; Lochner & Moretti, 2004), be more

active as citizens (Lochner, 2011), and to be healthier (Bossuyt

et al., 2004; Khang et al., 2004) and happier (Easterlin, 2003).

Factors negatively associated with poor educational outcomes are

generally consistent across not just Latin America, but the globe. Lack of

parental education is associated with lower attainment and higher dropout rates

from high school (Barnard, 2004; Lee & Bowen, 2006) and parental

involvement and expectations play an important role (Arends-Kuenning

& Duryea, 2006; Driessen et al., 2005; Choi, 2008). Socioeconomic status is

strongly associated with academic achievement (Nam & Juang,

2009; Rearon, 2011; Altschul,

2012; Pfeffer, 2018; Ziol-Guest & Lee, 2016) and

belonging to an ethnic minority group is also strongly associated with poorer

educational outcomes in many countries (Gillborn & Mirza, 2000; Kao &

Thompson, 2003; Murillo, 2003; Archer & Francis, 2006). Other factors such

as the level of urbanisation is found to be

negatively associated with educational outcomes in developing countries for a

variety of reasons including the higher cost per student of providing education

in rural areas (Behrman et al., 1999; Gould, 2007).

It’s been argued that in Latin America, unlike in many developing

countries, gender is no longer associated with educational outcomes. Female

students are reported to have not faced disadvantage in terms of enrolment

across the region for over 30 years (Ahuja & Filmer, 1995) and have even

begun to overtake male students, receiving equal or higher grades than males

(Grant & Behrman, 2010). Along with factors mentioned above, child labour is found to be a significant predictor of poor

educational outcomes including enrolment, attendance, grade repetition and

attainment (Montmarquette et al., 2007; Heymann et al., 2013; Psacharopoulos,

1997; Assaad et al., 2010; Putnick

& Bornstein, 2016; Eckstein & Wolpin, 1999;

Parent, 2006; Gunnarsson et al., 2006). Latin American countries have large

numbers of children working with varying legislation (Appendix 1) as well as

social programmes in place aimed at reducing this

practice.

In terms of enforcement of child labour laws,

none of the Latin American countries in this study have a

sufficient number of labour inspectors as per technical

advice from the International Labour Organisation (ILO) of a ratio of 1 inspector for every

15,000 workers. In Colombia, Dominican Republic and

Peru there are less than half the recommended number of inspectors (ILAB,

2020). Not all countries have data available on the number of inspections

conducted and even fewer report the number of child labour violations found and for which penalties were

imposed and subsequently collected. In Chile and the Dominican Republic

two of the countries for which we have some data, all child labour

violations found had penalties imposed; however, in Chile less than half of

these penalties were collected. In Colombia of 247 labour

violations found in 2017, only 15 had penalties imposed (ILAB, 2020).

All countries have various social programmes

aimed at reducing child labour. These include programmes which strengthen the employability of family

members of at risk children (Walking Together for the Eradication of Child

Labor, Chile), conditional cash transfer programs (More Families in Action,

Colombia; Let’s Get Ahead Program, Costa Rica; the Together Program, Peru),

work and study programmes (I Study and Work,

Uruguay), extension of the school day (Dominican Republic), educational and

psychological help to at risk families (Carabayllo

Project, Peru), targeting children in rural areas (Huánuco Project Peru; Houses

of Joy Costa Rica) and education on children’s rights (Present Against Child

Labor, Colombia) (ILAB, 2020).

One of the challenges in studying child labour

is that of defining child labour itself. The

difficulty in arriving at a uniform definition is the fact that child labour intersects with local contextual and cultural

factors. This complexity intensifies as we approach the adolescent years of the

child, when his or her physical capacity to undertake work coincides with the

most crucial secondary school years and, in many countries, legal working age.

Minimum working age legislation often comes in the form of ratification of the

Minimum Age Convention set forth by the ILO, who proffer their own definition

of child labour.

The ILO notes that not all work undertaken by children can be classified

as “child labour” and define it only as, “work that

deprives children of their childhood, their potential and their dignity, and

that is harmful to physical and mental development and/or interferes with their

schooling.” (ILO, 1996). Some kinds of work undertaken by children and

adolescents are in fact considered positive. The ILO includes in this category

activities such as household chores, helping in a family business or earning an

allowance outside of school hours. They note that these activities “contribute

to children’s development and to the welfare of their families; they provide

them with skills and experience and help to prepare them to be productive

members of society during their adult life.” (ILO, 1996)

Whether specific forms of work outside of the above can be considered

‘child labour’ is contingent on the age of the child,

the nature and hours of the work undertaken and the working conditions and the

cultural and legal contexts. This is then contingent on the individual country

and the sector the work falls under (ILO, 1996). The ILO specifically considers

work child labour if it has an adverse effect on a

child’s education by “depriving them of the opportunity to attend school;

obliging them to leave school prematurely; or requiring them to attempt to

combine school attendance with excessively long and heavy work.” (ILO, 1996).

The definition of child labour is a complex

one, and data available does not always allow operationalisation

of it as per ILO guidelines. For the purpose of this

analysis, child labour is understood as any labour undertaken by children (who in this study are aged

15) before or after school. Similar to previous

studies on child labour in Latin America (Gunnarsson

et al., 2006; Psacharopoulos, 1997), this study lacks

information on the nature of work undertaken as well as the hours.

There is a potential argument made for a broader definition of child labour which is not tied to the specific nature of the work

nor the number of hours. The image of a child working for long hours outside

the home that informs legislation and social programmes

aimed at its reduction, is not the profile of child labourers

in many countries and particularly misrepresents the labour

of girls (Assaad et al., 2010). Children are often

engaged in work that is not captured by traditional definitions of work (i.e.

market work) for example unpaid agricultural work in family enterprises.

In doing so, research ignores the potential for responsibilities inside the

household to effect educational attainment, in fact any work which interferes

with human capital production that would benefit children and society should be

considered (Putnick & Bornstein, 2016; Assaad et al., 2010). In addition, this kind of unpaid

household work is said to be gendered and traditional definitions of work

significantly misrepresent the work undertaken by girls (Putnick

& Bornstein, 2016; Levison, 2000). This complexity can only be understood

and tackled, if need be, by studying child labour in

each context and examining the factors local forces that shape the

process.

Therefore, it is important to empirically study how child labour interacts with influential factors such as gender.

This paper sets out to achieve just that in the context of Latin America. It

seeks to explore the trends and effects in/of participation of child in labour forms categorised broadly

as household labour and non-household labour and its effect on education.

2. Literature review

There are various reasons posited for children’s’ participation in work.

Using simultaneous equation models fitted to Indian data, Rosenzweig and

Evenson (1977) analysed family decision making

regarding fertility and the allocation of children’s time to labour and education. They concluded that a high return on

raw child labour as opposed to investment in skills

acted as a motivation for the creation of large families. In analysis of data

from Venezuela, Psacharopoulos (1997) found a similar

trend - that the decision to work was associated with a larger family size.

However, data from Botswana on the activities of youth led Chernikovsky

et al. (1985) to conclude that there is in fact no trade-off between children’s

schooling and fertility.

Child’s gender, familial wealth and composition and rural dwelling are

important predictors of child labour. In an analysis

of data from Latin America Psacharopoulos (1997)

found working children were mostly male, indigenous, and from poorer

female-headed households and their earnings contributed a significant amount of

household income, amounting to 13% and 27% in Bolivia and Venezuela

respectively. Analysis of Canadian data showed that student gender and

education of parents most significantly predicted students’ preference for labour market participation over schooling. As well as male

students and students with parents with no post-secondary education, female

students with children and students from single parent families were also

overrepresented among those who drop out to pursue work (Montmarquette

et al., 2007). In addition, several studies have found that residing in an

urban area reduces the probability of children undertaking paid work (Psacharopoulos, 1996; Assaad et

al., 2010).

Macro factors like minimum wage and levels of unemployment are strongly

associated with child labour. The decision to drop

out of school to pursue work is significantly affected by minimum wage

(measured in real terms) - when students who are unsure as to whether to finish

high school can earn a high minimum wage in the labour

market, they tend to conclude there is little to gain from continuing their

education (Montmarquette et al., 2007). As well as a

high minimum wage, low unemployment rate can also cause students who may not be

inclined to drop out, to do so under these particular

conditions. Montmarquette et al. (2007)

evidence this in their finding that the effect of these macroeconomic variables

was stronger for those who express a preference for schooling (and therefore

under normal conditions would not be inclined to drop out).

Studies of various Latin American countries in

particular have shown that legislation has little effect on children’s

involvement in the labour force. Psacharopoulos’

(1997) analysis revealed significant participation in the labour

market among children who should be prevented from it by compulsory education

or working age legislation. Similar evidence was found in Brazil by Bargain and

Boutin (2017) and in data from 59 countries including Venezuela, the Dominican

Republic and Bolivia by Edmonds and Shrestha (2012). Legislation often fails in

eliminating child labour in its entirety as

legislation does not cover the entire economy or only applies to specific

activities or sectors (Boockmann, 2010). A ban that

applies only to certain sectors also leads to a reduction in child wages due to

the subsequent excess supply of child labour in

sectors not enforcing the ban (Basu & Van, 1998).

In addition if productivity and wages are higher in

the sector where the legislation is enforced (e.g. industry) it pushes children

into low paid low productivity employment such as agriculture. Households rely

on this income need to maintain it. This means that more hours would be worked in order for household wealth not to be negatively affected

meaning less time allocated to education.

The reduction of income also has a subsequent effect on other

children within the family – although substantial working hours represent a

clear detriment to a child’s education, their earnings (which as previously

discussed can be as high as 27% of household income) increase the probability

that their siblings will attend school (Basu & Tzannatos, 2003). If wages are depressed, instead of more

hours worked by one child, budget-constrained households may send more children

to work, and legislation has had the exact opposite of the desired

effect. A rise in adult wages is needed to offset that negative effects

on household wealth to avoid the above consequences (Boockmann,

2010). This is also the case if the financial consequences of a ban (penalties

or bribes) are shouldered by families (Basu &

Van, 1998).

2.1 Household Labour

In addition the prohibition of child labour (through minimum legal working age laws) is rarely

applied uniformly across all activities. Thus, it may in fact merely lead to

the reallocation of child labour into unregulated

sectors such as family businesses or work happening inside the household where

these laws do not apply or are even more difficult to enforce (Bargain

& Boutin, 2017). Using a two-sector model of employment in which

legislation completely eliminates child labour, Basu (2005) found that a

ban via minimum age legislation in this model instead pushed children into

unregulated work. There are three conditions identified by Edmonds and

Shrestha (2012) as necessary for sector reallocation to be neutral after a ban

in the regulated sector. Firstly, that child and adult labour

are exact substitutes subject to a productivity shifter (based on Basu and Van’s (1998) ‘substitution axiom’). The second

condition is ‘non-saturation’ - that adult and child labour

can be easily substituted between productive tasks within the household.

Thirdly is the need for ‘competitive adult labour

markets’ – the free movement of adult labour between

the household and the labour market, otherwise

children’s work may merely be moved inside the home. Despite this, the

paid work undertaken by children outside the home has received the most

empirical attention (Putnick & Bornstein, 2016)

and literature on child labour often ignores the

potential for responsibilities inside the household to affect educational

attainment.

Levison (2000) further argues that the traditional definition of work

used to define child labour distinguishes arbitrarily

between activities that are similar. She gives the example of food preparation,

which if happening in a market stall or unpaid in a family enterprise is

considered work, but the same activity is not considered work if undertaken for

the purpose of household consumption. In the context of labour

force statistics or national accounts the distinction between household /

domestic work and market work is useful but causes biases when trying to

understand the effect of child labour on schooling

(Levison, 2000). Small jobs or chores may be beneficial for children, but the

issue is with all work, whether included in the traditional definition or not,

that interferes with children’s education or wellbeing (Assaad

et al. 2010).

2.2 Gender

As previously discussed, the definition used when assessing the

relationship between children’s work and educational attainment matters

greatly, particularly for girls - gender differences in both the incidence and

determinants of work are misrepresented when a traditional definition of work

(i.e. market work) is used (Levison 2000). Overall, for middle- and low-income

countries, there are higher rates of girls’ labour

inside the home and higher rates of labout inside the

home for boys, which often reflects “macrosystem-level gender inequality” (Putnick & Bornstein, 2016, p5). The high amount of

household labour carried out by girls can be

attributed to the cultural expectation that girls will be mothers and

homemakers and thus early involvement in household work acts as preparation for

these adult roles (Assaad et al., 2010).

As well as cultural, the reason is economic - in a number of the low- to

middle- income countries studied by Putnick &

Bornstein (2016) the levels of education and rates of employment are much lower

for women than for men - in the face of these limited economic opportunities

for adult women, parents may encourage girls to assume responsibilities within

the household to prepare them for their likely adult role as a homemaker. It

can also be considered a rational decision by girls and adolescents themselves,

who are aware of their incredibly limited access to the paid labour market (Assaad et al.,

2010). In the same vain, boys’ work outside the home allows them to

develop skills that may apply to their adult work. In countries with better

national gender equality, participation of boys and girls in excessive chores

is similar (Putnick & Bornstein, 2016).

2.3 Educational outcomes

Studies have examined the effect of hours worked on educational outcomes

measured by enrolment, attendance, drop out / graduation rates, grade

repetition, years of schooling and in few cases, test results. Household and

non-household labour has been found to negatively

affect both enrolment and attendance (Beegle et al., 2009; Assad et al., 2010).

In a study of developing countries only, Guarcello et

al. (2008) found that working children faced an attendance disadvantage of 10%

or above in 56 out of 60 countries, and in 10 of those countries the

disadvantage was as high as 30%. Working children also have a disadvantage in

total years of schooling compared to non-working children. In Latin American

countries, the difference in educational attainment between nonworking and

working children begins as young as aged six and then increases rapidly - by

the age of 14 (legal working age) Venezuelan working children have a deficiency

of 2 years and Bolivian working children 1.4 years (rising to 2.5 by the age of

18) (Psacharopoulos, 1997).

However, measuring educational outcomes in this way has limitations.

Attendance, enrolment and even years of schooling do not measure learning.

Children might continue to attend school every day due to compulsory schooling

legislation however working children may be too fatigued to study effectively

in school nor have the time nor energy to study afterwards (Gunnarsson et al.,

2006); the effects of which are not captured by these measures.

Various studies have found a strong link between work and high school

drop-out rates (Parent, 2006; Montmarquette et al.,

2007; Eckstein and Wolpin, 1999). While dropping out

of high school to pursue work may be due to economic necessity of the household

with child income often accounting for large percentage of a household’s income

(Psacharopoulos, 1997). Working during high school

may cause a child to lag behind in their schoolwork to

the point where dropping out in favour of entering

the labour market full time is preferable (Eckstein

and Wolpin, 1999). However, assessing educational

outcomes as completion (graduation) or non-completion (drop-out) of high school

does not take into account working children who stay

in school and their possible lower achievement and the limit that places on

future pursuits. It has been noted in several studies including Marsh (1991)

and Barone (1993) that young people working more than 20 hours per week while

in school were much less likely to pursue higher education.

Educational attainment can be assessed through grade attainment.

Although grade failure and repetition are associated with the same causal

factors as children’s participation in the labour

market, working almost doubles the likelihood of failing a grade (Psacharopoulos, 1997). Beegle et al. (2009) found

that child labour was significantly associated with a

reduction of the highest grade attained. Although grade attainment may be a more

nuanced measure than high school completion, the main limitation is the

difficulty of cross-country comparison due to substantial difference in

schooling across countries including the way in which grade attainment is

assessed. In their study of Latin America, Gunnarsson et al. (2006) used

results from mathematics and literacy tests and found that children who almost

never work had a 22% and 27% advantage in mathematics and language respectively

over working children. Although the use of test scores is arguably a better

measure of educational outcomes as it measures learning, the use of pooled

regression does not sufficiently address the issue of cross-country invariance.

3. Significance of the study

Previous studies examining the effect of child labour

have largely focused on school enrolment, attendance, dropouts, grade

repetition and aspirations. These can be considered proxies, and proxies for

only schooling, not addressing the actual goal of schooling itself – learning.

There is also a dearth in exploitating the

large-scale cross-country surveys which offer a valuable snapshot on the latest

trends in child labour, gender and education.

This study would help bridge the gap in literature by examining the

association between child labour, and its interaction

with gender, and educational attainment measured via test scores. In addition

to that, it gives a more comprehensive picture of the trends in Latin America

by giving a comparative analysis involving various countries. There are very

few studies focused solely on Latin America, and the majority of those that

have done so, or included Latin America in aggregate or pooled data, have used

data from more than two decades ago. Latin America has undergone rapid change

over the last 20 years, and although inequality persists, it has been declining

in many countries (López-Calva & Listig, 2010).

However, whilst access to primary and secondary education has been expanded,

access to tertiary education, the next stage in Latin America’s “educational

upgrading” (Grynspan, 2010, p.vii), could be affected

due to low educational attainment in secondary schools, (López-Calva & Listig, 2010), precisely the outcome variable measure in this

study, and a crucial factor that studies examining purely schooling would

miss.

This study exploits the variance in labour participation

levels, and student learning levels, both within and between countries to

estimate its association. The study employs multilevel analysis, which accounts

for clustering, to identify the contribution (positive or negative) and

significance of child labour, and its association

with gender, in shaping student test scores. This study aims to add robust

empirical evidence to the body of knowledge on the status of child labour participation and its effect on child’s education.

This evidence is important through its uniqueness - it does not originate from

a study focused exclusively on child labour or

household survey but from a school survey focusing on education.

4. Research questions

This study uses large-scale datasets from OECD’s PISA to explore the

trends and effects of labour practices among

15-year-old children on their education outcomes in seven Latin American

countries. The study exploits PISA 2015 survey data which captures if the

student is engaged in household or non-household labour

in all of the seven Latin American countries. It seeks

to examine the effects of child labour participation

(for household and non-household labour separately)

on learning achievements in each of the seven countries, after controlling for

various individual, household and school effects. Additionally, the study also

examines if the participation and effects of participation in labour is moderated by individuals’ gender.

1. What are the patterns in child labour

participation (in household and non-household labour)

across the sample of Latin American countries? How is it distributed along the

lines of gender?

2. Does participation in household or/and non-household labour have any significant influence on student’s learning

levels? If so, what is the magnitude of effect in each country?

3. Does gender moderate the effect of labour

participation on student attainment?

5. Data

and methods

There were 72 countries in total which participated in PISA in 2015 and

eight from Latin America. They include Brazil, Chile, Costa

Rica, Colombia, Dominican Republic,

Mexico, Peru and Uruguay. PISA follows a complex sampling design strategy. The

schools are selected using systematic-random PPS (probability proportional to

size) sampling. In the next stage, students who are 15 years old are randomly

selected from each school. There is data collected at the student level,

teacher level and school level from all the sampled schools and students (OECD,

2017).

Along with collecting information about student and home background,

PISA also surveys if students participate in household and non-household labour activities. These are the main variables of interest

in this study. They are captured for each student in the sample in all the PISA

participating countries from Latin America. Each of the students is

administered an assessment to capture his or her learning levels in

mathematics, science, reading, financial literacy and collaborative problem

solving. Due to the length of the assessment, the student undertakes only a

part of the test in each subject and based on their performance, the final

scores are imputed as plausible values. The mathematics scores are chosen as

proxy for student learning and achievement in this study. With mathematics

achievement as the outcome, two-level hierarchical regression models are

constructed for each country with student at one level and school at another

level.

Hierarchical regression analysis is chosen over OLS linear regression

model to account for the clustering effects of students in a school (Goldstein

2011). This is due to the correlation between student performances from the

same school. Hierarchical models would produce unbiased and robust estimates

taking into consideration that student scores in the sample are not independent

of each other. The inferences made from the analysis of PISA 2015 can be generalisable to a country level due to the representative

sample and the sampling weights included as part of the analysis. In order to account for the imputation uncertainty derived

from the PISA complex assessment design, the ten plausible values provided in

the data set for the maths scores were used

simultaneously in all the analyses (Rutkowski, et al., 2010). Furthermore,

following the procedure suggested by Rutkowski and colleagues (2010), each

level was weighted separately for all the models

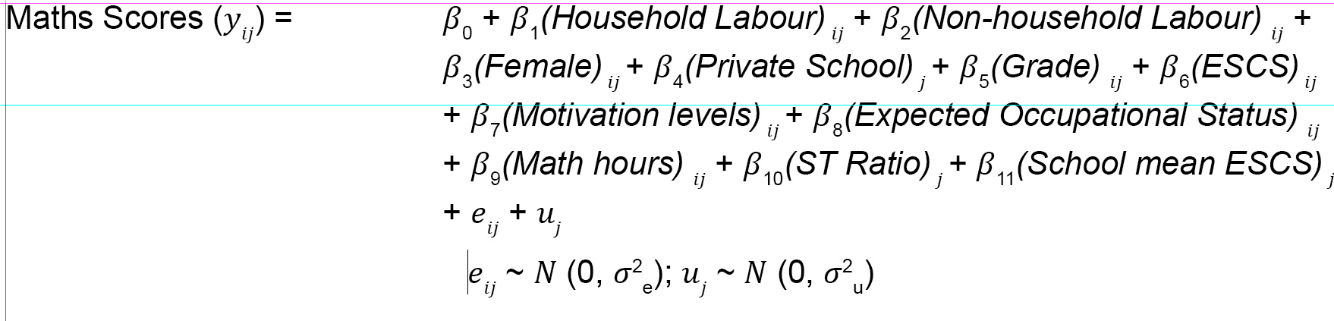

The first model (M1) is constructed for each of the seven countries, to examine the effect

of participation in labour activities on learning

achievement in mathematics:

While the variables of interest are mainly household, non-household labour and gender of the student, it is necessary to

control for various student and school-level characteristics. The school-level

variables accounted for in the modelling are the type of school (public or

private), the Student-Teacher ratio of the school and most importantly the

average of social, economic and cultural statuses (ESCS) of all sampled

children in the school. The individual level characteristics controlled for in

the above and below equations are the grade in which the student is studying,

motivational levels, aspiration levels (desired occupation status) and the

number of hours dedicated in total to study the subject of assessment (mathematics).

These covariates are chosen from literature as they have shown to demonstrate a

significant contribution in explaining the variance of the outcome variable

(student achievement). The Model (M1) assists in answering the second research question on

the significance and effect of labour participation

in student learning.

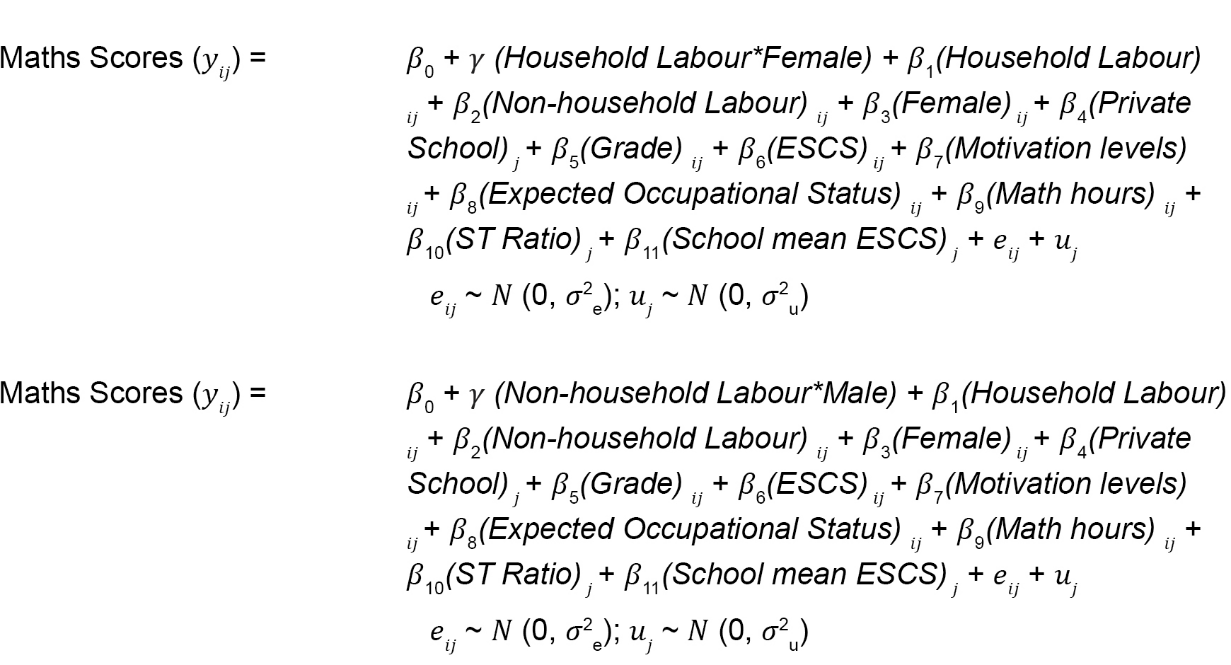

In order, to answer the third research problem of this paper, the

following models (M2) and (M3) are constructed. In order to examine if

gender moderates the effect of labour participation

on student learning, an interaction term, between household labour

and female dummy, between non-household labour and

male dummy, is added to the above model.

Female is included as a dummy in model 2 (M2) as it is often observed that girls engage more in

household labour and it would be plausible to examine

if female moderates the effect in the case of household labour

participation. Likewise, following the similar reasoning, male is added as a

dummy for model 3 (M3) in the case of non-household labour. These

models are similarly constructed for each country with the controls from first

model (M1) intact.

6 Results

The trends and distribution of participation in labour

activities, in household and non-household domains, in seven[i] Latin American countries are demonstrated by the

following descriptive statistics in (Table 1) and (Table 2).

Table 1

|

Country |

Household Labour (%) |

Non Household Labour (%) |

||

|

|

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Chile |

33.56 |

66.44 |

75.45 |

24.55 |

|

Colombia |

22.98 |

77.02 |

55.54 |

44.46 |

|

Costa Rica |

34.16 |

65.84 |

80.79 |

19.21 |

|

Dom Rep. |

15.63 |

84.37 |

58.66 |

41.34 |

|

Mexico |

17.46 |

82.54 |

70.5 |

29.5 |

|

Peru |

10.3 |

89.7 |

68.24 |

31.76 |

|

Uruguay |

20.66 |

79.34 |

67.59 |

32.41 |

Source: authors’ descriptive statistics from PISA

2015.

All the Latin American countries studied here have at least 65% of the

sample taking part in household labour and not more

than 45% involved in non-household labour. The

highest participation in household labour is found in

Peru, followed closely by Dominican Republic and Mexico. In the case of

non-household labour, Colombia has the highest

percentage, immediately followed by Dominican Republic. Costa Rica has the

lowest participation of the sample in both household and non-household labour. Not far below Costa Rica, Chile is found to have

the second lowest participation levels in both domains. However, it cannot be

said if having a higher or lower percentage of children involved in labour, has (or does not have) an effect on one’s

education. It remains to be seen if labour

participation has any actual effect (positive or negative) on student’s

education and how this could be shaped by different contextual factors.

Table 2

|

Country |

Gender |

Household Labour |

Non-Household Labour |

||

|

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

||

|

Chile |

Male |

1,046 |

2,019 |

2,129 |

921 |

|

Female |

1,026 |

2,083 |

2,502 |

586 |

|

|

Columbia |

Male |

1,251 |

3,906 |

2,531 |

2,623 |

|

Female |

1,255 |

4,492 |

3,514 |

2,217 |

|

|

Costa Rica |

Male |

946 |

1,692 |

1,976 |

657 |

|

Female |

898 |

1,862 |

2,377 |

378 |

|

|

Dominican Rep |

Male |

311 |

1,341 |

800 |

836 |

|

Female |

234 |

1,600 |

1,222 |

589 |

|

|

Mexico |

Male |

634 |

2,634 |

2,022 |

1,237 |

|

Female |

521 |

2,827 |

2,630 |

710 |

|

|

Peru |

Male |

317 |

2,503 |

1,680 |

1,134 |

|

Female |

240 |

2,346 |

1,994 |

576 |

|

|

Uruguay |

Male |

474 |

1,781 |

1,296 |

938 |

|

Female |

523 |

2,047 |

1,922 |

605 |

|

Source: authors’ descriptive statistics from PISA

2015.

Therefore, the first research question is answered through the

descriptive statistics by depicting an overall picture of percentages and

frequencies of participation rates in household and non-household labour activities and how they are split based on gender.

The results of the hierarchical linear models for each country are represented

below. The estimates and their standard errors of variables of interest and

other student and school level covariates are listed in Table 3.

Table 3

|

Student achievement |

Chile |

Colombia |

Costa Rica |

Dom Rep. |

Mexico |

Peru |

Uruguay |

|

Household Labour |

-1.31 |

-4.51 |

1.25 |

3.18 |

1.56 |

-8.27** |

-10.74*** |

|

(-3.11) |

(-2.75) |

(-2.86) |

(-4.32) |

(-3.49) |

(-4.07) |

(-3.69) |

|

|

Non-Household Labour |

-27.21*** |

-23.29*** |

-18.13*** |

-25.59*** |

-22.09*** |

-25.20*** |

-25.14*** |

|

(-3.47) |

(-2.41) |

(-3.14) |

(-2.97) |

(-2.84) |

(-2.7) |

(-3.54) |

|

|

Female |

-28.90*** |

-26.34*** |

-23.22*** |

-12.68*** |

-13.86*** |

-20.53*** |

-25.64*** |

|

(-3) |

(-2.71) |

(-3.17) |

(-3.03) |

(-2.33) |

(-2.61) |

(-3.88) |

|

|

Private |

-4.84 |

0.68 |

-2.59 |

2.82 |

-11.5 |

-3.75 |

-1.76 |

|

(-9.79) |

(-7.36) |

(-10.21) |

(-11.24) |

(-9.11) |

(-7.57) |

(-9.56) |

|

|

Grade |

30.82*** |

23.70*** |

21.63*** |

17.97*** |

18.48*** |

22.74*** |

27.89*** |

|

(-3.07) |

(-1.14) |

(-2.02) |

(-1.8) |

(-3.89) |

(-1.41) |

(-2.21) |

|

|

ESCS |

9.50*** |

5.47*** |

6.64*** |

5.78*** |

4.15*** |

6.96*** |

8.55*** |

|

(-1.58) |

(-1.6) |

(-1.2) |

(-1.88) |

(-1.25) |

(-1.58) |

(-1.96) |

|

|

Motivational Level |

1.19 |

8.69*** |

2.29 |

5.33** |

6.39*** |

11.03*** |

9.21*** |

|

(-1.55) |

(-2.01) |

(-2.1) |

(-2.13) |

(-1.84) |

(-1.72) |

(-1.69) |

|

|

Exp Occupational Status |

0.55*** |

0.22*** |

-0.08 |

0.07 |

0.28*** |

0.58*** |

0.36*** |

|

(-0.1) |

(-0.07) |

(-0.06) |

(-0.1) |

(-0.07) |

(-0.08) |

(-0.08) |

|

|

Maths hours |

-0.11 |

0.49 |

1.63 |

-0.76 |

0.79 |

0.17 |

2.33** |

|

(-0.42) |

(-0.53) |

(-1.1) |

(-0.47) |

(-0.69) |

(-0.44) |

(-1.12) |

|

|

Student-Teacher Ratio |

0.78 |

-0.33 |

0.05 |

0.15 |

-0.08 |

0.36* |

-0.12 |

|

(-0.58) |

(-0.23) |

(-0.19) |

(-0.2) |

(-0.21) |

(-0.21) |

(-0.24) |

|

|

School mean (ESCS) |

30.43*** |

19.92*** |

22.06*** |

26.42*** |

17.69*** |

19.94*** |

32.18*** |

|

(-5.22) |

(-5.6) |

(-4.37) |

(-7.82) |

(-4.46) |

(-4.12) |

(-6.35) |

|

|

Constant |

430.44*** |

448.70*** |

456.64*** |

377.08*** |

436.17*** |

400.88*** |

476.60*** |

|

(-13.69) |

(-11.24) |

(-8.56) |

(-16.12) |

(-12.01) |

(-11.33) |

(-11.86) |

|

|

lns1_1_1 |

3.31*** |

3.23*** |

3.29*** |

3.09*** |

3.27*** |

3.16*** |

3.27*** |

|

(-0.09) |

(-0.08) |

(-0.1) |

(-0.19) |

(-0.11) |

(-0.08) |

(-0.09) |

|

|

lnsig_e |

4.09*** |

4.03*** |

3.96*** |

3.91*** |

4.10*** |

4.08*** |

4.12*** |

|

(-0.01) |

(-0.01) |

(-0.01) |

(-0.03) |

(-0.02) |

(-0.02) |

(-0.02) |

|

|

Sample size (n=) |

4,529 |

7,647 |

4,803 |

2,370 |

5,734 |

4,869 |

3,782 |

Standard errors in parentheses *** p<0.01, **

p<0.05, * p<0.1

Source: authors’ work.

Household labour is not found to be

significant (with 95% confidence levels) in shaping students learning except in

the contexts of Peru and Uruguay. In these contexts, participating in household

labour is shown to have a higher magnitude of effect

than ones socio-economic and cultural status. Non-household labour

participation, however, is found to be highly significant (with 99% confidence

levels) and has a remarkable negative effect on student learning. This pattern

is found in all the seven Latin American countries. These findings lead to the

next question if the effects of non-household labour

and household labour (in Peru and Uruguay) on student

achievement are moderated by the individual’s gender. In other words, the

question can be rephrased as to understand if the gender effects (of being a

female) on achievement, as seen in the above table, is influenced/moderated by

male or female’s participation in labour activities.

The following tables (Table 4 and Table 5) aid in addressing the follow up

question.

Table 4

|

Student achievement |

Chile |

Colombia |

Costa Rica |

Dom Rep. |

Mexico |

Peru |

Uruguay |

|

Female*Household Labour |

-2.87 |

-1.95 |

-0.88 |

0.2 |

1.14 |

-2.32 |

8.87 |

|

(-5.47) |

(-5.26) |

(-4.01) |

(-7.35) |

(-5.53) |

(-6.91) |

(-6.78) |

|

|

Female |

-26.94*** |

-24.82*** |

-22.64*** |

-12.84** |

-14.80*** |

-18.44*** |

-32.58*** |

|

(-4.87) |

(-5.14) |

(-3.8) |

(-6.3) |

(-5.37) |

(-6.98) |

(-6.5) |

|

|

Household Labour |

0.15 |

-3.47 |

1.71 |

3.09 |

1.06 |

-7.24 |

-15.70*** |

|

(-3.96) |

(-4.04) |

(-3.51) |

(-6.01) |

(-4.54) |

(-5.02) |

(-5.74) |

|

|

Non-Household Labour |

-27.31*** |

-23.34*** |

-18.17*** |

-25.58*** |

-22.07*** |

-25.23*** |

-24.88*** |

|

(-3.45) |

(-2.42) |

(-3.15) |

(-2.97) |

(-2.83) |

(-2.72) |

(-3.58) |

|

|

ESCS |

9.51*** |

5.46*** |

6.63*** |

5.78*** |

4.15*** |

6.95*** |

8.49*** |

|

(-1.58) |

(-1.61) |

(-1.2) |

(-1.88) |

(-1.26) |

(-1.58) |

(-1.95) |

|

|

Private |

-4.87 |

0.7 |

-2.57 |

2.82 |

-11.5 |

-3.77 |

-1.77 |

|

(-9.76) |

(-7.36) |

(-10.24) |

(-11.24) |

(-9.11) |

(-7.56) |

(-9.62) |

|

|

GRADE |

30.82*** |

23.70*** |

21.62*** |

17.97*** |

18.47*** |

22.75*** |

27.93*** |

|

(-3.07) |

(-1.14) |

(-2.02) |

(-1.8) |

(-3.89) |

(-1.41) |

(-2.21) |

|

|

Motivational Level |

1.18 |

8.67*** |

2.29 |

5.33** |

6.40*** |

11.01*** |

9.20*** |

|

(-1.55) |

(-2) |

(-2.1) |

(-2.13) |

(-1.84) |

(-1.72) |

(-1.69) |

|

|

Exp Occupational Status |

0.55*** |

0.22*** |

-0.08 |

0.07 |

0.28*** |

0.58*** |

0.36*** |

|

(-0.1) |

(-0.07) |

(-0.06) |

(-0.1) |

(-0.07) |

(-0.08) |

(-0.08) |

|

|

Maths hours |

-0.11 |

0.49 |

1.62 |

-0.76 |

0.79 |

0.17 |

2.31** |

|

(-0.42) |

(-0.53) |

(-1.1) |

(-0.47) |

(-0.69) |

(-0.44) |

(-1.12) |

|

|

Student-Teacher Ratio |

0.78 |

-0.33 |

0.05 |

0.15 |

-0.08 |

0.36* |

-0.11 |

|

(-0.58) |

(-0.23) |

(-0.19) |

(-0.2) |

(-0.21) |

(-0.21) |

(-0.24) |

|

|

School mean (ESCS) |

30.40*** |

19.88*** |

22.04*** |

26.42*** |

17.68*** |

19.95*** |

32.18*** |

|

(-5.21) |

(-5.6) |

(-4.38) |

(-7.82) |

(-4.47) |

(-4.11) |

(-6.39) |

|

|

Constant |

429.61*** |

447.79*** |

456.35*** |

377.15*** |

436.56*** |

399.98*** |

480.28*** |

|

(-13.9) |

(-11.78) |

(-8.55) |

(-16.42) |

(-12.25) |

(-11.51) |

(-12.41) |

|

|

lns1_1_1 |

3.31*** |

3.23*** |

3.29*** |

3.09*** |

3.27*** |

3.16*** |

3.27*** |

|

(-0.09) |

(-0.08) |

(-0.1) |

(-0.19) |

(-0.11) |

(-0.08) |

(-0.09) |

|

|

lnsig_e |

4.09*** |

4.03*** |

3.96*** |

3.91*** |

4.10*** |

4.08*** |

4.12*** |

|

(-0.01) |

(-0.01) |

(-0.01) |

(-0.03) |

(-0.02) |

(-0.02) |

(-0.02) |

|

|

Sample size (n=) |

4,529 |

7,647 |

4,803 |

2,370 |

5,734 |

4,869 |

3,782 |

Standard errors in parentheses *** p<0.01, **

p<0.05, * p<0.1

Source: authors’ work.

Table 5

|

Student achievement |

Chile |

Colombia |

Costa Rica |

Dom Rep. |

Mexico |

Peru |

Uruguay |

|

Male*Non-Household Labour |

0.57 |

-2.4 |

-14.00*** |

-4.36 |

-1.88 |

-5.87 |

-11.98** |

|

(-6.76) |

(-3.62) |

(-4.96) |

(-5.14) |

(-4.97) |

(-4.68) |

(-6.05) |

|

|

Female |

-28.75*** |

-27.46*** |

-25.72*** |

-14.27*** |

-14.37*** |

-22.24*** |

-29.39*** |

|

(-3.37) |

(-3.03) |

(-3.27) |

(-3.17) |

(-2.59) |

(-2.83) |

(-4.57) |

|

|

Household Labour |

-1.31 |

-4.42 |

1.39 |

3.41 |

1.59 |

-8.12** |

-10.49*** |

|

(-3.13) |

(-2.77) |

(-2.86) |

(-4.35) |

(-3.5) |

(-4.09) |

(-3.68) |

|

|

Non-Household Labour |

-27.53*** |

-22.18*** |

-9.66** |

-23.37*** |

-20.96*** |

-21.73*** |

-19.07*** |

|

(-4.58) |

(-2.67) |

(-4.46) |

(-4.17) |

(-4.01) |

(-3.79) |

(-4.83) |

|

|

ESCS |

9.50*** |

5.47*** |

6.63*** |

5.80*** |

4.16*** |

6.99*** |

8.48*** |

|

(-1.57) |

(-1.6) |

(-1.2) |

(-1.88) |

(-1.25) |

(-1.58) |

(-1.96) |

|

|

Private |

-4.83 |

0.65 |

-2.89 |

2.92 |

-11.48 |

-3.7 |

-2.07 |

|

(-9.79) |

(-7.35) |

(-10.14) |

(-11.25) |

(-9.11) |

(-7.57) |

(-9.67) |

|

|

GRADE |

30.82*** |

23.71*** |

21.56*** |

17.97*** |

18.48*** |

22.72*** |

27.84*** |

|

(-3.07) |

(-1.14) |

(-2.02) |

(-1.8) |

(-3.89) |

(-1.4) |

(-2.21) |

|

|

Motivational Level |

1.19 |

8.68*** |

2.25 |

5.37** |

6.37*** |

11.07*** |

9.24*** |

|

(-1.55) |

(-2) |

(-2.1) |

(-2.13) |

(-1.84) |

(-1.71) |

(-1.7) |

|

|

Exp Occupational Status |

0.55*** |

0.22*** |

-0.09 |

0.06 |

0.28*** |

0.58*** |

0.35*** |

|

(-0.1) |

(-0.07) |

(-0.06) |

(-0.1) |

(-0.07) |

(-0.08) |

(-0.08) |

|

|

Maths hours |

-0.11 |

0.49 |

1.7 |

-0.73 |

0.8 |

0.18 |

2.36** |

|

(-0.43) |

(-0.53) |

(-1.1) |

(-0.47) |

(-0.69) |

(-0.44) |

(-1.12) |

|

|

Student-Teacher Ratio |

0.78 |

-0.34 |

0.05 |

0.15 |

-0.08 |

0.37* |

-0.12 |

|

(-0.58) |

(-0.23) |

(-0.19) |

(-0.2) |

(-0.21) |

(-0.21) |

(-0.24) |

|

|

School mean (ESCS) |

30.42*** |

19.89*** |

21.99*** |

26.24*** |

17.66*** |

19.82*** |

32.14*** |

|

(-5.21) |

(-5.59) |

(-4.38) |

(-7.83) |

(-4.46) |

(-4.13) |

(-6.39) |

|

|

Constant |

430.39*** |

449.43*** |

457.80*** |

377.82*** |

436.43*** |

401.57*** |

478.92*** |

|

(-13.75) |

(-11.29) |

(-8.6) |

(-16.12) |

(-11.91) |

(-11.35) |

(-12.06) |

|

|

lns1_1_1 |

3.31*** |

3.23*** |

3.29*** |

3.09*** |

3.27*** |

3.16*** |

3.27*** |

|

(-0.09) |

(-0.08) |

(-0.1) |

(-0.19) |

(-0.11) |

(-0.08) |

(-0.09) |

|

|

lnsig_e |

4.09*** |

4.03*** |

3.96*** |

3.91*** |

4.10*** |

4.08*** |

4.12*** |

|

(-0.01) |

(-0.01) |

(-0.01) |

(-0.03) |

(-0.02) |

(-0.02) |

(-0.02) |

|

|

Sample size (n=) |

4,529 |

7,647 |

4,803 |

2,370 |

5,734 |

4,869 |

3,782 |

Standard errors in parentheses *** p<0.01, **

p<0.05, * p<0.1

Source: authors’ work.

Table 4 shows that there is no significant difference in achievement

between males and females, on average, engaging in household labour across all 7 countries. The magnitude of the

difference, although non-significant, is negligible. There is also no difference

in outcomes between males who participate in household labour

compared to those who do not except in the context of Uruguay. Boys engaged in

household labour in Uruguay scored 15.7 points lower,

on average. In Peru, they scored 7.24 points lower than boys who did not engage

in household labour although the difference is not

statistically significant. The findings are consistent for household labour participation effects from table 3 (which showed the

average of both males and females) where only Uruguay and Peru had significant

differences.

The results from Table 5 show that gender does not moderate the effects

of engagement in non-Household labour on achievement

outcomes except in the context of Costa Rice and Uruguay. The penalty of

participating in non-household labour is

significantly higher for males over females in Costa Rica and Uruguay (-14 and

-11.98 points higher respectively). However, on an average for both males and

females, participating in non-household labour is

associated with lower outcomes (from table 3 and table 4). Table 5 reiterates

the same findings with respect to the effects of household labour

participation from table 3 and also additionally

demonstrates the significantly lower outcomes among females who engage in

non-household labour compared to those who do not.

Some of the broad observations which speak to literature regarding

student education status are that, unlike in many other developing country

contexts, attending a private school has shown no significant effect on average

in all the above Latin American countries. The results also point broadly to

poor quality education offered in secondary schools, as number of hours

invested in studying by the student does not show any significant gains in

their learning except marginally in Uruguay.

Lastly, although gender does not moderate the effects of household labour participation on student learning, it still remains as an influential category. The magnitude of

influence gender has in shaping learning is at least 2.5 to 5 times more than

that of socio-economic and cultural status, depending on the country. Girls are

found to consistently underperform in comparison to boys in every Latin

American country without exception.

7. Conclusion

This study used international largescale assessment data (PISA) to

highlight the trends and patterns in child labour

participation in household and non-household activities in the seven Latin

American countries. The results show a high level of participation, at least

65% in household activities and not less than 20% in non-household activities,

in all countries in the sample. Furthermore, participation in household labour is not found to significantly affect students

learning in majority of the countries except Peru and Uruguay.

Participation in non-household labour is shown

to significantly hamper students’ progress in learning across all of the seven countries of Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica,

Dominican Republic, Mexico, Peru and Uruguay. This finding is in line with the

findings of previous literature that non-household labour

is a serious problem plaguing Latin American. Where previous studies have

focused on the effect of child labour on school

dropouts, repetitions of grade, attendance and years of schooling, this study

contributes to knowledge by specifically demonstrating the magnitude of effect

of participation in such activities on students learning levels, relative to

other variables. It further adds how gender fails to moderate the household labour effects on learning and also

in the case of non-household labour effects in

majority of countries (except Costa Rica and Uruguay).

It does however point to gender as strongly associated with educational

attainment, with girls underperforming boy across all countries despite

literature positing that Latin America had in fact closed this gap, with female

students even beginning to outperform males (Ahuja & Filmer, 1995; Grant

& Behrman, 2010).

The strength of the study stems from the nature of survey data. The

sample is representative for all the countries and measures of learning

achievement are statistically sophisticated through inclusion of plausible

values and appropriate sampling weights. This adds to the strength of generalisability of the results. The trends in

participation levels, association and moderation between variables highlighted

in the paper can be said to hold true for the entire population of 15-year olds in the above Latin American countries. Another

strength of the study is the use of hierarchical modelling. In many of the

empirical studies involving child labour, it is not

common to account for the clustering of children’s characteristics to estimate

the effects of child labour on chosen outcomes.

The main weakness of the study is the measurement of participation in

household and non-household activities using a binary scale. It collapses

various forms of labour and duration of labour into a single category thereby impeding the further

deciphering of the nature of activities across various countries or

socio-economic categories. However, this lack of detail can be justified as the

focus of the study is exclusively on education and we exploited the opportunity

of the dataset capturing participation in labour

albeit in a rudimentary form.

This study does not establish any causal relationship between participation

in child labour (in household or non-household

activities), or gender, or their interaction on the student achievement. This

paper gives a potentially valuable perspective into the reality of the nature

of association and trends across countries. However, a more rigorous

identification strategy is needed to address the endogeneity problem to infer

causality.

At age 15 (the age of all students participating in PISA) participation

in the labour market is legal in all Latin American

countries (Appendix 1). This is often only with authorisation

from the inspectorate or local authority, but given the previously discussed

lack of inspectors, it is doubtful whether the work conditions or hour limits

are being enforced. This study shows that even potentially legal child labour may play a significant role in the regions’ low

educational attainment and should not be neglected in future work in the area.

The empirical trends and analysis can potentially contradict some of the

theoretical understanding on the gendered nature of household activities or

non-household activities. It challenges claims that household and non-household

activities have differing effects for male and female education outcomes

(except for Costa Rica and Uruguay in the contexts of non-household labour). There is inequality between genders in terms of

achievement levels and also between those who participate in child labour (more significantly in non-household activities) and

those who do not; however, the harmful effects of participating in

non-household labour is not connected to gender. This

is because the participation in non-household activities is undesirable

irrespective of one’s gender and there are other spheres of discrimination or

decision-making which are potentially driving the inequality in learning

outcomes between males and females that demand attention. Therefore, the focus

for further research or policy ought to include other spheres of influence, or

socio-economic dimensions to address the gender inequality in achievement

levels.

[i] Brazil

is omitted from the list due to large amount (approx. 45%) of missing data in

the category of labour participation in household and

non-household domains.

It is also important to note that this study doesn’t use the latest PISA

2018 data as the survey no longer includes variables pertaining to any forms of

labour.

Appendix 1

|

Chile |

Colombia |

Costa Rica |

Dominican Rep. |

Mexico |

Peru |

Uruguay |

|||

|

School compulsory until |

17 |

15 |

16 |

13 |

17 |

16 |

14 |

||

|

Minimum Age for Work |

15 |

15 |

15 |

14 |

15 |

14 |

15 |

||

|

Minimum Age for Hazardous Work |

18 |

18 |

18 |

18 |

18 |

18 |

18 |

||

|

Ratification of International Conventions on Child Labour |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

||

Source: ILAB, 2020.

References

Ahuja,

V. & Filmer, D. (1995). Educational attainment in development countries:

New estimates and projections disaggregated by gender. Journal

of Educational Planning and Administration X(3):

229-254

Altschul,

I. (2012). Linking socioeconomic status to the academic achievement of Mexican

American youth through parent involvement in education. Journal

of the Society for Social Work and Research, 3(1), 13-30.

Archer,

L., & Francis, B. (2006). Understanding minority

ethnic achievement: Race, gender, class and’success’. Routledge.

Arends-Kuenning, M., &

Duryea, S. (2006). The effect of parental presence, parents’ education, and

household headship on adolescents’ schooling and work in Latin America. Journal

of Family and Economic Issues, 27(2), 263-286.

Assaad, R., Levison, D., & Zibani, N. (2010). The effect of domestic work on girls’ schooling:

Evidence from Egypt. Feminist Economics, 16(1), 79-128.

Bargain, O., & Boutin, D. (2017). Minimum age

regulation and child labor: New evidence from Brazil

Barnard,

W. M. (2004). Parent involvement in elementary school and educational

attainment. Children and youth services review,

26(1), 39-62.

Barone, F. J. (1993). The effects of part-time

employment on academic performance. NASSP Bulletin, 77(549), 67-73.

Basu, K.

(2005). Global labour standards and local freedoms.

In WIDER perspectives on global development (pp. 175-200). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Basu, K.,

& Tzannatos, Z. (2003). The Global Child Labor

Problem: What do we know and what can we do?. The

world bank economic review, 17(2),

147-173.

Basu, K.,

& Van, P. H. (1998). The economics of child labor. American

economic review, 412-427.

Beegle, K., Dehejia, R.,

& Gatti, R. (2009). Why should we care about

child labor? The education, labor market, and health consequences of child

labor. Journal of Human Resources, 44(4), 871-889

Behrman, J., Duryea, S., & Székely,

M. (1999). Schooling investments and aggregate conditions: A

household-survey-based approach for Latin America and the Caribbean. IDB-OCE

Working Paper, (407).

Boockmann, B. (2010). The effect of ilo minimum age

conventions on child labor and school attendance: Evidence from aggregate and

individual-level data. World Development, 38(5), 679-692.

Bossuyt, N., Gadeyne, S., Deboosere,

P., & Van Oyen, H. (2004). Socio-economic inequalities in health expectancy

in Belgium. Public health, 118(1), 3-10.

Card,

D. (1999). The causal effect of education on earnings. In Handbook

of labor economics (Vol. 3, pp.

1801-1863). Elsevier.

Chernikovsky, D.,

Lucas, R. E., & Mueller, E. (1985). The household economy of

rural Botswana: An African case. The World Bank.

Choi, A. (2018). De padres a hijos: expectativas y

rendimiento académico en España. Presupuesto y gasto público, 90,

13-32.

Driessen, G., Smit, F., & Sleegers, P. (2005). Parental

involvement and educational achievement. British

educational research journal, 31(4), 509-532.

Easterlin,

R. A. (2003). Explaining happiness. Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences, 100(19), 11176-11183.

Eckstein, Z., & Wolpin,

K. I. (1999) ‘Why youths drop out of high school: the impact of preferences,

opportunities, and abilities,’ Econometrica 67, 1295–339

Edmonds, E. V., & Shrestha, M. (2012). The impact

of minimum age of employment regulation on child labor and schooling. IZA

Journal of Labor Policy, 1(1), 14.

Gillborn,

D., & Mirza, H. S. (2000). Educational Inequality: Mapping Race, Class and

Gender. A Synthesis of Research Evidence.

Gould, E. D. (2007). Cities, workers, and wages: A

structural analysis of the urban wage premium. The

Review of Economic Studies, 74(2),

477-506

Grant,

M. J., & Behrman, J. R. (2010). Gender gaps in educational attainment in

less developed countries. Population and development

review, 36(1), 71-89.

Grynspan, R. (2010). Foreword. In Declining inequality

in Latin America: A decade of progress? (pp. Vi-Vii).

Brookings Institution Press.

Guarcello, L., Lyon, S., & Rosati, F. C. (2008). Child labor and education

for all: An issue paper. The journal of the History of Childhood and

Youth, 1(2), 254-266

Gunnarsson,

V., Orazem, P. F., & Sánchez, M. A. (2006). Child

labor and school achievement in Latin America. The

World Bank Economic Review, 20(1),

31-54.

Heymann, J., Raub, A., & Cassola, A. (2013). Does prohibiting child labor increase secondary school

enrolment? Insights from a new global dataset.

International Journal of Educational Research, 60, 38-45.

ILAB (2020). Findings on the Worst Forms

of Child Labor. U.S.

Department of Labor, Bureau of International Labor Affairs. Available at https://bit.ly/2Hwp3e2.

ILO (1996). What is child labour. International

Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC) Available at https://bit.ly/3oudwfR.

Khang, Y. H.,

Lynch, J. W., & Kaplan, G. A. (2004). Health inequalities in Korea: age-and

sex-specific educational differences in the 10 leading causes of death. International

Journal of Epidemiology, 33(2),

299-308.

Kao,

G., & Thompson, J. S. (2003). Racial and ethnic stratification in educational

achievement and attainment. Annual review of sociology, 29(1), 417-442.

Lee,

J.-S., & Bowen, N. K. (2006). Parent Involvement, Cultural Capital, and the

Achievement Gap Among Elementary School Children. American

Educational Research Journal, 43(2), 193–218. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312043002193

Levison, D. (2000). Children as economic agents. Feminist

Economics, 6(1), 125-134.

Lochner,

L. (2011). Non-production benefits of education: Crime,

health, and good citizenship (No.

w16722). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Lochner,

L., & Moretti, E. (2004). The effect of education on crime: Evidence from

prison inmates, arrests, and self-reports. American

economic review, 94(1), 155-189.

López-Calva, L. F., &

Lustig, N. C. (Eds.). (2010). Declining

inequality in Latin America: A decade of progress?. Brookings Institution Press.

Machin, S., Marie, O., & Vujić,

S. (2011). The crime reducing effect of education. The

Economic Journal, 121(552), 463-484.

Marsh, H. W. (1991). Employment during high school:

Character building or a subversion of academic goals?.

Sociology of education,

172-189.

Montmarquette, C., Viennot-Briot, N., & Dagenais, M.

(2007). Dropout, school performance, and working while in

school. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(4), 752-760.

Murillo, F. J.

(2003). Una panorámica de la investigación iberoamericana sobre eficacia

escolar. Revista

Electrónica Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 1(1).

Nam, Y., & Huang, J. (2009). Equal opportunity for

all? Parental economic resources and children’s educational attainment. Children

and Youth Services Review, 31(6),

625-634

OECD (2017). PISA 2015 assessment and

analytical framework: Science, reading, mathematic, financial literacy and

collaborative problem solving. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Publishing

Parent, D. (2006). Work while in high school in

Canada: its labour market and educational attainment

effects. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d’économique, 39(4), 1125-1150.

Pfeffer, F. T. (2018). Growing wealth gaps in

education. Demography, 55(3), 1033-1068

Psacharopoulos, G. (1997). Child labor versus educational attainment Some evidence

from Latin America. Journal of population economics, 10(4), 377-386.

Putnick, D. L., & Bornstein, M. H. (2016). Girls’ and boys’ labor and

household chores in low-and middle-income countries. Monographs

of the Society for Research in Child Development, 81(1), 104.

Reardon, S. F. (2011). The widening academic

achievement gap between the rich and the poor: New evidence and possible

explanations. In G. J. Duncan & R. J. Murnane (Eds.), Whither

opportunity? Rising inequality, schools, and children’s life chances (pp. 91–115). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation

Rosenzweig, M. R., & Evenson, R. (1977).

Fertility, schooling, and the economic contribution of children of rural India:

An econometric analysis. Econometrica:

journal of the Econometric Society, 1065-10.

Rutkowski, L., Gonzalez, E., Joncas,

M., & von Davier, M. (2010). International

large-scale assessment data: Issues in secondary analysis and reporting. Educational

Researcher, 39(2), 142-151.

Ziol-Guest,

K. M., & Lee, K. T. (2016). Parent income–based gaps in schooling:

Cross-cohort trends in the NLSYs and the PSID. AERA

Open, 2(2). https://doi.org/ 10.1177/2332858416645834.

How to Cite

Middel, A., Kameshwara, K. K., & Sandoval-Hernandez, A. (2020).

Exploring trends in the relationship between child labour,

gender and educational achievement in Latin America. Iberoamerican Journal of Education, 84(1), 85-108.

https://doi.org/10.35362/rie8413987